This meme reminds me a lot of Node as well. In this article, I’ll attempt to bring more clarity about how Node works under the hood from a concurrency and memory management point of view. After that, approach the performance topic of Node servers, and how its internals can affect it.

- Terminology

- Overview of Node’s concurrency model

- Overview of Node’s memory model

- Diagram and clarifications

Node under the hood

Terminology

Many words and concepts are thrown around when dealing with Node. Let’s define some of them:

Blocking operations

- Execute synchronously

- Meaning, until that operation is done, the thread’s call stack can pick up no other instructions

Non-blocking operations

- Execute asynchronously

- Meaning, while the operation is happening, other instructions can be picked up by the thread’s call stack

So, blocking/non-blocking operations are always strictly related to one specific thread.

Process: groups together the required resources (e.g. memory space) to execute a program

Thread:

- Parented by a process

- Handles the execution of instructions with the help of a program counter, registers, and a stack (aka call stack, thread stack)

- All threads of a process

- have their own program counter, registers, and stack

- share the memory space of the process i.e., faster interthread communication than interprocess

Memory heap: portion of memory with dynamically allocated data

I/O: refers to disk and network operations

Some disk operations: reading/writing a file

Some network operations:

- Doing HTTP requests

- Interacting with a database via a driver that acts as an API

Callback:

- A callback is a function passed to another function as an argument, to be called inside that function once some action is over

- More specifically to Node, callbacks enable asynchronous behavior, by defining the action that should be performed once the asynchronous operation is done

Thread-based servers:

- Handle each incoming request in a separate thread

- I/O is blocking/synchronous (i.e., the thread’s call stack is stuck until the I/O operation is finished)

- Based on throughput, the overhead cost can increase (if the thread pool is too small for the throughput, either a new thread has to be created, or the client waits for a thread to be released in the thread pool)

Event-based servers:

- Handle every incoming request in one main thread

- I/O is non-blocking/asynchronous on the main thread and managed by an event (i/o) loop

- This approach makes the assumption our server is I/O intensive instead of CPU intensive

- If we manage to avoid intensive computing, this approach gains an advantage over the thread-based servers, because it manages to avoid the thread overhead, by processing all requests in the same thread

Overview of Node’s concurrency model

At the core of Node’s concurrency is its event-based architecture with the event loop in the center. The event loop is either pooling for I/O events or looping through callback queues and emptying them.

By using one thread for incoming requests, we make use of events that signal incoming requests or the completion of asynchronous operations and are picked up by the event loop and executed one by one. The whole system hangs on the idea of fast-executing callbacks and not starving the event loop. Any time the event loop can’t empty its callback queues, client requests are blocked.

Event handlers are a type of callback, that is meant to be executed once an event is emitted.

Let’s follow an example where 5 HTTP requests come at the same time. In order to fulfill the requests, all we have to do in our handler is call the database for some data and return it to the client:

- For each incoming HTTP request, an event is emitted that has an event handler attached (the code we wrote to run for that specific endpoint)

- The event loop which continuously listens for events, takes in the HTTP request events and puts the event handlers in a queue, that gets emptied one by one

- Once event handlers get executed, we enter the code we wrote where we call the DB and send a response to the client

- Once we hit the line that does the DB request, non-blocking sockets come into play and enable us to execute other callbacks (this enables all 5 requests to get to this point)

- When the DB request started, an

EventEmitterobject is created, that will emit an event when there is a finality to the request (success or error) - When DB requests start completing, events start being emitted with their handlers (in this case, all they do is return the data we got from the DB)

- The events are being picked up by the event loop, put in a queue, and executed one by one

- Finally, we start sending responses to clients and finalize the requests

const express = require("express");

const app = express();

app.get("/users", async (_, res) => {

const users = await db.get('users')

res.json({ users });

});

app.listen(3000);

Now, we can look at lines like this const users = await db.get('users') in a different light. This await syntax is there only to help us give our endpoint handler a synchronous structure. The DB operation happens on the main thread and is non-blocking. In order for that await to return a value, the event loop has to actually execute the callback from the emitted event that signaled the finality of the request.

Overview of Node’s memory model

Node uses JavaScript which is a garbage-collected language, meaning, we don’t have to deal with memory deallocations. The job of the garbage collector is straightforward: identify unused memory allocations then release that memory so it could be further used.

The JavaScript engine that Node uses implements a generational garbage collector called Orinoco.

Orinoco:

- starts from the premise that most objects die young, which is true in the context of servers as well

- splits objects into different generations (young and old)

- young generation allocations are cheap, so is the algorithm cleaning it when it gets full

- if objects survive two GC cycles they’re moved to the old generation

- old generation has a bigger size, and most objects will die young anyway, so this space is rarely expected to need clean-up (if we write proper code that is not leaking memory)

- When the garbage collector runs, code does not

Diagram and clarifications

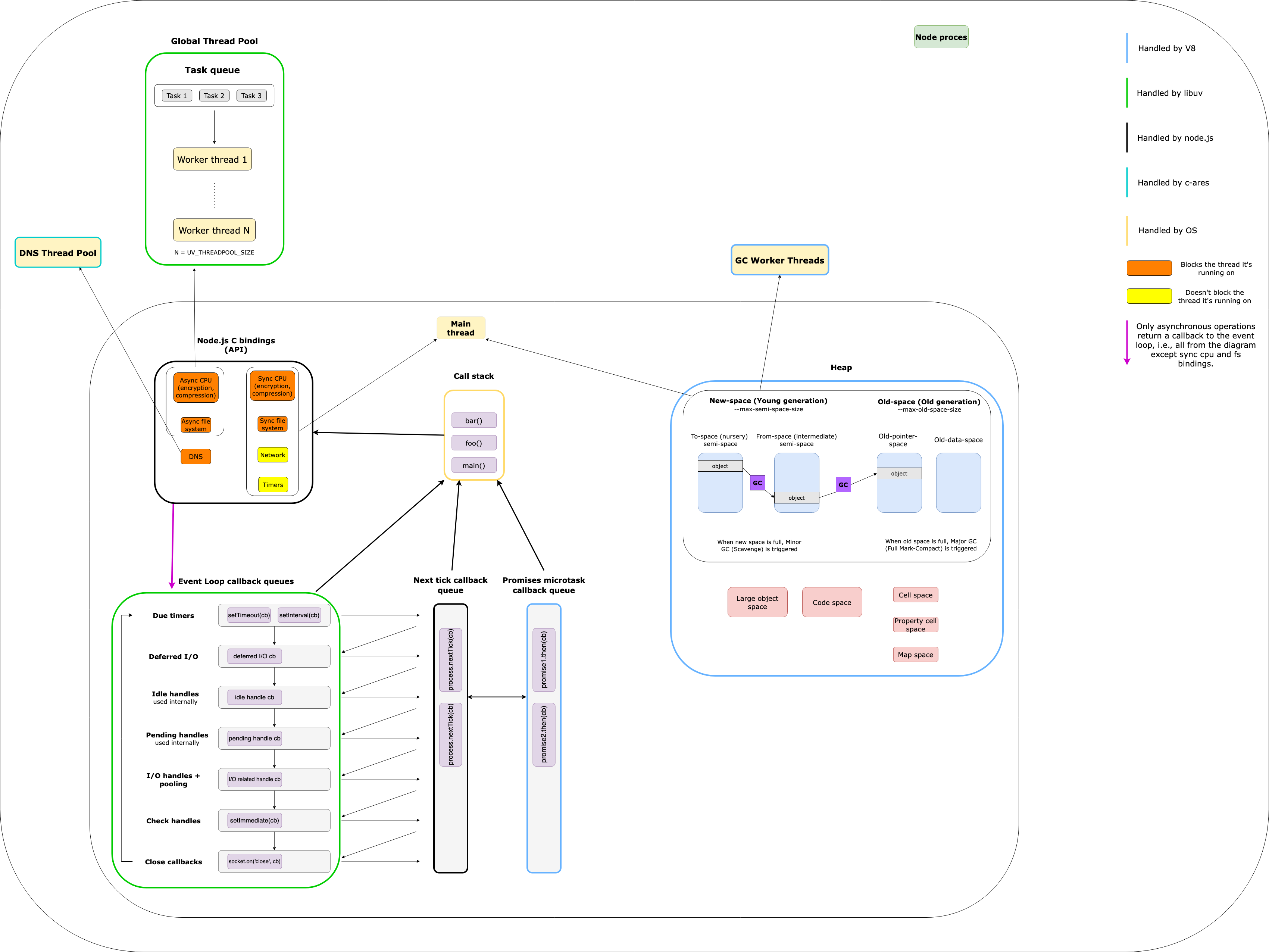

We can see that Node is more of a glue between external dependencies (V8, libuv, c-ares) that provides us APIs (e.g. http, fs) which are actually C bindings. These bindings are simply libraries that bind two programming languages, in our case they enable us to write for e.g. HTTP call in JavaScript, but under the hood that call is actually executed in C by libuv.

Let’s summarize each section of the diagram.

The callback queues

So, it’s not only the event loop that manages and executes callbacks from multiple queues. We also have the nextTick queue and the promise microtask queue. And all 3 of them are managed by different entities.

The queues have a specific order of execution:

nextTickqueue has the highest priority for executionpromisemicrotask queue second-highest- event loop queues third

Let’s follow some examples where the call stack finished execution and we find ourselves with populated callback queues:

First example

setTimeout(() => console.log('setTimeout 1 callback'), 0)

setTimeout(() => console.log('setTimeout 2 callback'), 0)

Promise.resolve().then(() => console.log('promise 1 callback'))

Promise.resolve().then(() => console.log('promise 2 callback'))

process.nextTick(() => console.log('nextTick 1 callback'))

process.nextTick(() => console.log('nextTick 2 callback'))

Logs:

nextTick 1 callback

nextTick 2 callback

promise 1 callback

promise 2 callback

setTimeout 1 callback

setTimeout 2 callback

In this case, the situation is clear. The nextTick queue has the highest priority and it empties first, then the promise one, and finally the event loop queue.

Second example

setTimeout(() => {

console.log('setTimeout 1 callback')

Promise.resolve().then(() => console.log('promise from setTimeout callback'))

process.nextTick(() => console.log('nextTick from setTimeout callback'))

}, 0)

setTimeout(() => console.log('setTimeout 2 callback'), 0)

Logs:

setTimeout 1 callback

nextTick from setTimeout callback

promise from setTimeout callback

setTimeout 2 callback

Even if two event loop callbacks are ready to execute, if, in the first callback, we define nextTick or promise callbacks, they take priority and execute before the second event loop callback.

Third example

Promise.resolve().then(() => {

console.log('promise 1 callback')

process.nextTick(() => console.log('nextTick 1 callback'))

})

Promise.resolve().then(() => console.log('promise 2 callback'))

Logs:

promise 1 callback

promise 2 callback

nextTick 1 callback

Even if nextTick has the highest priority, if we started to execute the promise queue, it will get emptied before executing the nextTick callbacks.

Conclusions:

nextTick,promise, and event loop is the priority order of the queues- Event loop queues will always execute one callback, then

nextTickandpromisequeues will be emptied - If we start executing from either

nextTickorpromisequeue, those queues will be emptied before executing callbacks from other queues - Because of this specific queue priority we can easily starve the event loop by making recursive

nextTickorpromisecalls

The heap

- V8 splits the young generation into two semi-spaces

- When one semi-space gets full, objects are moved into the other one (surviving the first GC cycle)

- If the moved objects survive one more GC cycle they get promoted to the old generation

- When young generation or old generation spaces become full their respective algorithm is triggered and releases memory

- The sizes for both spaces are customizable, this enables fine-tuning based on our particular use cases

Bindings and threads

Which thread handles which operation can be pretty confusing with Node.

- Network and timer operations run on the main thread and are non-blocking

- Synchronous APIs for compute or disk run on the main thread and are blocking the thread

- Asynchronous APIs for compute or disk run on threads from

libuvthread pool and are blocking the thread they’re running on - DNS operations run on threads from

c-aresthread pool and are blocking the thread they’re running on

Notes on performance

Cost and cascading effects

Let’s follow the cost of different operations in the context of thousands requests/second:

1. Endpoint that just returns a response

const express = require("express");

const app = express();

app.get("/", async (_, res) => {

res.json({ success: true });

});

app.listen(3000);

Benchmark result:

Requests per second: 9062.08 [#/sec] (mean)

Time per request: 11.035 [ms] (mean)

2. Adding O(N) operation, where N=1mil

const express = require("express");

const app = express();

app.get("/", async (_, res) => {

for (let i = 0; i <= 1000000; i++) {}

res.json({ success: true });

});

app.listen(3000);

Benchmark result:

Requests per second: 2313.30 [#/sec] (mean)

Time per request: 43.228 [ms] (mean)

Even if it is an empty for it still takes lots of CPU cycles to finish, meaning every request takes longer, and the call stack is stuck iterating loops than processing new request callbacks.

Even if a for with N=1mil might be far-fetched, you can easily get the same number of operations with an O(N^2) operation with N=1000.

3. Simulating a 50ms network call

const express = require("express");

const app = express();

app.get("/", async (_, res) => {

for (let i = 0; i <= 1000000; i++) {}

await new Promise((resolve) => {

setTimeout(resolve, 50);

});

res.json({ success: true });

});

app.listen(3000);

Benchmark result:

Requests per second: 1547.41 [#/sec] (mean)

Time per request: 64.624 [ms] (mean)

4. But, it’s totally normal to have endpoints that have more than one network call

const express = require("express");

const app = express();

app.get("/", async (_, res) => {

for (let i = 0; i <= 1000000; i++) {}

await new Promise((resolve) => {

setTimeout(resolve, 50);

});

await new Promise((resolve) => {

setTimeout(resolve, 50);

});

res.json({ success: true });

});

app.listen(3000);

Benchmark result:

Requests per second: 816.31 [#/sec] (mean)

Time per request: 122.503 [ms] (mean)

Just one extra network call halves our throughput.

5. Let’s add some work for the garbage collector

const express = require("express");

const app = express();

app.get("/", async (_, res) => {

let arr = [];

for (let i = 0; i <= 1000000; i++) {

arr.push(10);

}

await new Promise((resolve) => {

setTimeout(resolve, 50);

});

await new Promise((resolve) => {

setTimeout(resolve, 50);

});

res.json({ success: true });

});

app.listen(3000);

Benchmark result:

Requests per second: 85.87 [#/sec] (mean)

Time per request: 1164.554 [ms] (mean)

This caused the biggest hit on throughput. Every request allocated an array of one million elements, so the new-space gets full all the time, so the garbage collector will run the minor GC a lot, and when the garbage collector runs our code does not.

One key note from this examples is to think of cost in a cascading way. Our performance is measured in throughput not in isolated scenarios.

In a way, it’s kinda known that doing O(N^2) operations is not ideal performance-wise, and sequentially doing network requests will increase latency. But, what might fly under the radar is the cost of the garbage collector if we’re not careful of how we allocate memory. Every single memory allocation has some overhead, so we should approach them with care.

Also, that huge initial hit of performance from that O(N) operation is meant to signal the fragility of this event-based system. Its whole throughput depends on us executing callbacks quickly by avoiding intensive CPU operation or expensive synchronous APIs that block the thread.

As a final note for this section, the purpose of these benchmarks is in no way meant to say that you suddenly shouldn’t do network calls anymore or for loops, but, always be aware of their cost, and if possible minimize it:

- fewer or parallel network calls

- better complexity for our algorithms

- smaller memory footprint/request

API and workers

Not every decision that impacts performance is related to improving algorithms complexity or minimizing network calls. Sometimes we have to make delimitations between what operations must happen in the server before giving the client a response, and what operations can be outsourced to a worker.

Sign-up example

Let’s say we launch a new app that already has a lot of hype and we expect lots of people to sign-up at the same time when we tweet that the app is live. Every time a client would hit the sign-up endpoint we would create a user in the database and send an confirmation email to the user. The email sending operation we outsource to a third-party API.

Related to third-party APIs:

- we have no idea of the locality of the server we’re hitting when calling those APIs (like we know for our database that we can keep in the same zone)

- that API also has certain rate limits

So we can find ourselves where we have a 100ms call to a third-party API (or get 429 errors), for a call that is not critical to happen exactly in that moment. We can easily just create a user in the database, with a field verified: false, use a message queue, and have a worker pick up the message and call the API (and also implement some retry mechanism in case of 429 errors).

The frontend can confirm to the user that it was created and that an email confirmation is coming. Even if our system somehow fails and we lose that message and the user doesn’t get the email, he can still just press a button (“send email again) that initiates another email-sending operation.

This example illustrates how a simple tweak in the logic of the endpoint can have drastic improvements for our throughput. Inevitably there will be endpoints with lots of operations and lots of traffic and at some point, we will run out of optimizations. Then all we’re left to do is try and outsource some of the operations to a worker.

Conclusion

Node in a way reminds me of NoSQL databases. As long as you follow the precise way they’re meant to be used, you can get better performance than traditional relational databases.

Understanding the concurrency and memory model of Node is absolutely critical, especially because it uses an event-based architecture and one CPU-intensive operation can absolutely wreck our throughput by impacting all incoming requests.

Thinking about cost in a cascading way can also help a lot because it makes us more aware of operations that would normally fly under the radar (like memory allocations).

This article just scratched the surface, check references to go more in-depth.

References:

https://nodejs.org/en/docs/guides/blocking-vs-non-blocking

https://nodejs.org/en/docs/guides/event-loop-timers-and-nexttick

https://nodejs.org/en/docs/guides/dont-block-the-event-loop

https://docs.libuv.org/en/v1.x/design.html

https://docs.libuv.org/en/v1.x/threadpool.html#threadpool

https://berb.github.io/diploma-thesis/original/043_threadsevents.html

A Deep Dive Into the Node js Event Loop - Tyler Hawkins

https://stackoverflow.com/questions/61550822/why-node-js-spins-7-threads-per-process

https://v8.dev/blog/trash-talk

https://jayconrod.com/posts/55/a-tour-of-v8-garbage-collection

https://v8.dev/blog/free-garbage-collection

https://deepu.tech/memory-management-in-v8/