about_node

In this article I’ll discuss about how Node works under the hood by focusing on its concurrency and memory models, then talk about performance when writing APIs.

Concurrency and garbage

Terminology

Many words and concepts are thrown around when dealing with Node. Let’s define some of them:

Blocking operations execute synchronously, i.e., the thread cannot execute other instructions until the operation is done.

Non-blocking operations execute asynchronously, i.e., the thread can execute other instructions while the operation is in progress.

Generally, when dealing with Node we consider operations blocking/non-blocking only related to the main thread where the event loop runs. Meaning, we can consider an operation non-blocking in the Node world while that operation is simply offloaded to a worker thread and blocking that thread.

A process groups together the required resources (e.g. memory space) to execute a program.

Threads:

- Parented by a process

- Handle the execution of instructions with the help of a program counter, registers, and a call stack (all three independent for all threads)

- Share the memory space of the process, i.e., faster interthread communication than interprocess

Memory heap: portion of memory with dynamically allocated data

I/O: disk (e.g. reading/writing a file) and network (e.g. doing HTTP requests) operations

Callback:

- A callback is a function passed to another function as an argument, to be called inside that function once some action is finalised

- More specifically to Node, callbacks enable asynchronous behavior, by defining the action that should be performed once the asynchronous operation is done

Thread-based servers:

- Handle each incoming request in a separate thread

- I/O is blocking/synchronous (i.e., the thread’s call stack is stuck until the I/O operation is finished)

- Based on throughput, the overhead cost can increase (if the thread pool is too small for the throughput, either a new thread has to be created, or the client waits for a thread to be released in the thread pool)

Event-based servers:

- Handle every incoming request in one main thread

- I/O is non-blocking/asynchronous on the main thread and managed by an event (I/O) loop

- This approach makes the assumption our server is I/O intensive instead of CPU intensive

- If we manage to avoid intensive computing, this approach gains an advantage over the thread-based servers, because it manages to avoid the thread overhead, by processing all requests in the same thread

Concurrency model

At the core of Node’s concurrency is its event-based architecture with the event loop in the center. The event loop is either pooling for I/O events or looping through callback queues and executing them (i.e. sending them to the call stack).

By using one thread for incoming requests, we make use of events that signal incoming requests or the completion of asynchronous operations and are picked up by the event loop and executed one by one. The whole system hangs on the idea of fast-executing callbacks and not starving the event loop. If at any time a callback takes too long to finish that means no other client requests are being processed.

Event handlers are a type of callback, that is meant to be executed once an event is emitted.

Let’s follow an example where 5 HTTP requests come at the same time. In order to fulfill the requests, all we have to do in our handler is call the database for some data and return it to the client:

- For each incoming HTTP request, an event is emitted that has an event handler attached (the code we wrote to run for that specific endpoint)

- The event loop which continuously listens for events, takes in the HTTP request events and puts the event handlers in a queue, that gets emptied one by one

- Once event handlers get executed, we enter the code we wrote where we call the DB and send a response to the client

- Once we hit the line that does the DB request, non-blocking sockets come into play and enable us to execute other callbacks (this enables all 5 requests to get to this point)

- When the DB request started, an

EventEmitterobject is created, that will emit an event when there is a finality to the request (success or error) - When DB requests start completing, events start being emitted with their handlers (in this case, all they do is return the data we got from the DB)

- The events are being picked up by the event loop, put in a queue, and executed one by one

- Finally, we start sending responses to clients and finalize the requests

const express = require("express");

const app = express();

app.get("/users", async (_, res) => {

const users = await db.get('users')

res.json({ users });

});

app.listen(3000);

Now, we can look at lines like this const users = await db.get('users') in a different light. This await syntax is there only to help us give our endpoint handler a synchronous structure. The DB operation happens on the main thread and is non-blocking. In order for that await to return a value, the event loop has to actually execute the callback from the emitted event that signaled the finality of the request.

Memory model

Node uses JavaScript which is a garbage-collected language, meaning, we don’t have to deal with memory deallocations. The job of the garbage collector is straightforward: identify unused memory allocations then release that memory so it could be further used.

The JavaScript engine that Node uses implements a generational garbage collector called Orinoco.

Orinoco:

- starts from the premise that most objects die young, which is true in the context of servers as well

- splits objects into different generations (young and old)

- young generation allocations are cheap, so is the algorithm cleaning it when it gets full

- if objects survive two GC cycles they’re moved to the old generation

- old generation has a bigger size, and most objects will die young anyway, so this space is rarely expected to need clean-up (if we write proper code that is not leaking memory)

- When the garbage collector runs, code does not

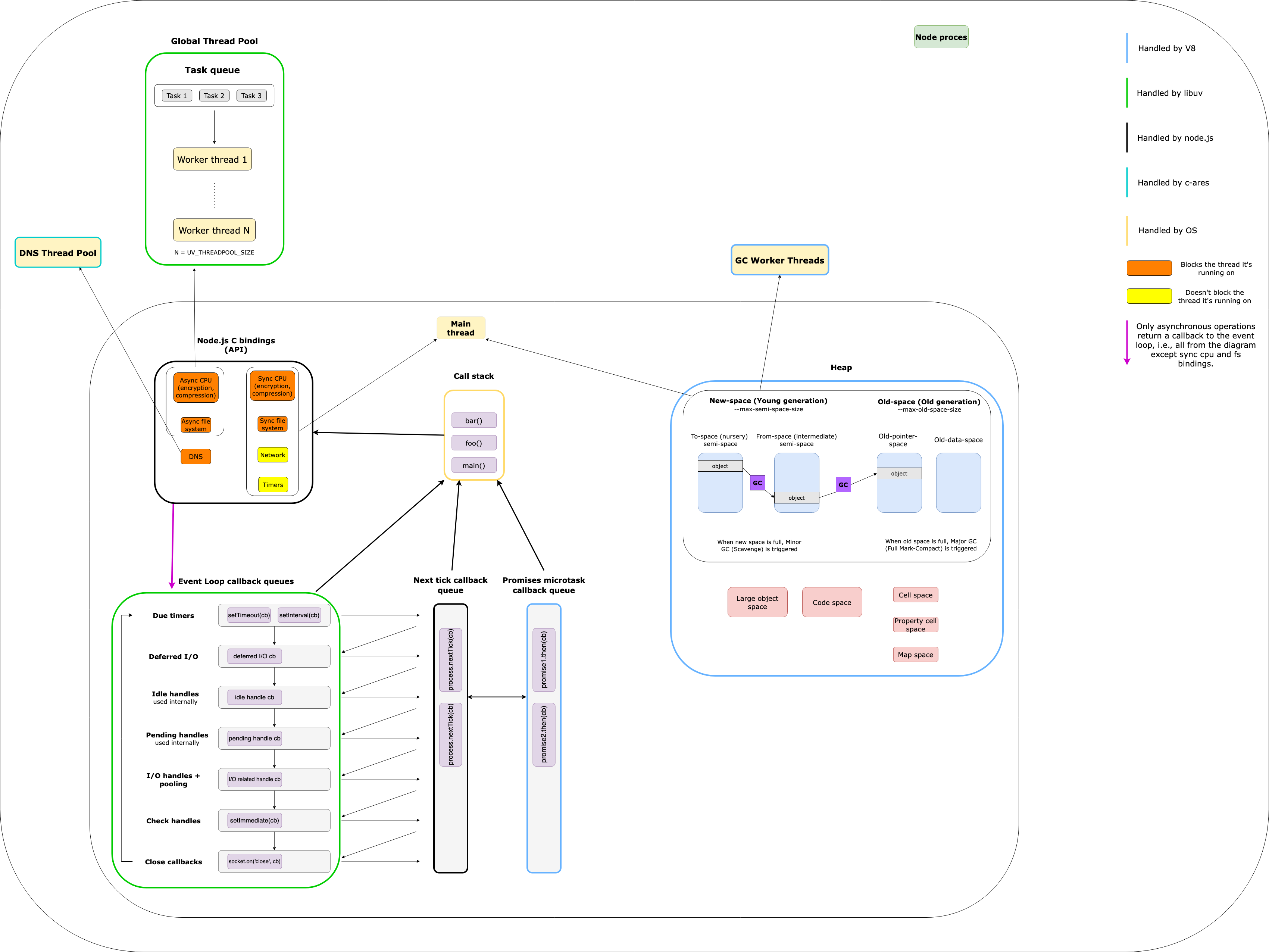

Diagram and clarifications

We can see that Node is more of a glue between external dependencies (V8, libuv, c-ares) that provides us APIs (e.g. http, fs) which are actually C bindings. These bindings are simply libraries that bind two programming languages, in our case they enable us to write for e.g. HTTP call in JavaScript, but under the hood that call is actually executed in C by libuv.

Let’s summarize each section of the diagram.

The callback queues

So, it’s not only the event loop that manages and executes callbacks from multiple queues. We also have the nextTick queue and the promise microtask queue. And all 3 of them are managed by different entities.

The queues have a specific order of execution:

nextTickqueue has the highest priority for executionpromisemicrotask queue second-highest- event loop queues third

Let’s follow some examples where the call stack finished execution and we find ourselves with populated callback queues:

First example

setTimeout(() => console.log('setTimeout 1 callback'), 0)

setTimeout(() => console.log('setTimeout 2 callback'), 0)

Promise.resolve().then(() => console.log('promise 1 callback'))

Promise.resolve().then(() => console.log('promise 2 callback'))

process.nextTick(() => console.log('nextTick 1 callback'))

process.nextTick(() => console.log('nextTick 2 callback'))

Logs:

nextTick 1 callback

nextTick 2 callback

promise 1 callback

promise 2 callback

setTimeout 1 callback

setTimeout 2 callback

In this case, the situation is clear. The nextTick queue has the highest priority and it empties first, then the promise one, and finally the event loop queue.

Second example

setTimeout(() => {

console.log('setTimeout 1 callback')

Promise.resolve().then(() => console.log('promise from setTimeout callback'))

process.nextTick(() => console.log('nextTick from setTimeout callback'))

}, 0)

setTimeout(() => console.log('setTimeout 2 callback'), 0)

Logs:

setTimeout 1 callback

nextTick from setTimeout callback

promise from setTimeout callback

setTimeout 2 callback

Even if two event loop callbacks are ready to execute, if, in the first callback, we define nextTick or promise callbacks, they take priority and execute before the second event loop callback.

Third example

Promise.resolve().then(() => {

console.log('promise 1 callback')

process.nextTick(() => console.log('nextTick 1 callback'))

})

Promise.resolve().then(() => console.log('promise 2 callback'))

Logs:

promise 1 callback

promise 2 callback

nextTick 1 callback

Even if nextTick has the highest priority, if we started to execute the promise queue, it will get emptied before executing the nextTick callbacks.

Conclusions:

nextTick,promise, and event loop is the priority order of the queues- Event loop queues will always execute one callback, then

nextTickandpromisequeues will be emptied - If we start executing from either

nextTickorpromisequeue, those queues will be emptied before executing callbacks from other queues - Because of this specific queue priority we can easily starve the event loop by making recursive

nextTickorpromisecalls

The heap

- V8 splits the young generation into two semi-spaces

- When one semi-space gets full, objects are moved into the other one (surviving the first GC cycle)

- If the moved objects survive one more GC cycle they get promoted to the old generation

- When young generation or old generation spaces become full their respective algorithm is triggered and releases memory

- The sizes for both spaces are customizable, this enables fine-tuning based on our particular use cases

Bindings and threads

Which thread handles which operation can be pretty confusing with Node.

- Network and timer operations run on the main thread and are non-blocking

- Synchronous APIs for compute or disk run on the main thread blocking it

- Asynchronous APIs for compute or disk run on threads from

libuvthread pool and are blocking the thread they’re running on - DNS operations run on threads from

c-aresthread pool and are blocking the thread they’re running on

Performance

Even though this topic is hugely vast, there are some basic points that we can follow and get good performance out of most APIs:

- Write optimal code (algorithmic complexity, network trips, memory footprint)

- Offload appropriate operations to workers

- Cache as much as possible

Cost and cascading effects

Let’s follow the cost of different operations in the context of thousands requests/second:

1. Endpoint that just returns a response

const express = require("express");

const app = express();

app.get("/", async (_, res) => {

res.json({ success: true });

});

app.listen(3000);

Benchmark result:

Requests per second: 9062.08 [#/sec] (mean)

Time per request: 11.035 [ms] (mean)

2. Adding O(N) operation, where N=1mil

const express = require("express");

const app = express();

app.get("/", async (_, res) => {

for (let i = 0; i <= 1000000; i++) {}

res.json({ success: true });

});

app.listen(3000);

Benchmark result:

Requests per second: 2313.30 [#/sec] (mean)

Time per request: 43.228 [ms] (mean)

Even if it is an empty for it still takes lots of CPU cycles to finish, meaning every request takes longer, and the call stack is stuck iterating loops than processing new request callbacks.

Even if a for with N=1mil might be far-fetched, you can easily get the same number of operations with an O(N^2) operation with N=1000.

3. Simulating a 50ms network call

const express = require("express");

const app = express();

app.get("/", async (_, res) => {

for (let i = 0; i <= 1000000; i++) {}

await new Promise((resolve) => {

setTimeout(resolve, 50);

});

res.json({ success: true });

});

app.listen(3000);

Benchmark result:

Requests per second: 1547.41 [#/sec] (mean)

Time per request: 64.624 [ms] (mean)

4. But, it’s totally normal to have endpoints that have more than one network call

const express = require("express");

const app = express();

app.get("/", async (_, res) => {

for (let i = 0; i <= 1000000; i++) {}

await new Promise((resolve) => {

setTimeout(resolve, 50);

});

await new Promise((resolve) => {

setTimeout(resolve, 50);

});

res.json({ success: true });

});

app.listen(3000);

Benchmark result:

Requests per second: 816.31 [#/sec] (mean)

Time per request: 122.503 [ms] (mean)

Just one extra network call halves our throughput.

5. Let’s add some work for the garbage collector

const express = require("express");

const app = express();

app.get("/", async (_, res) => {

let arr = [];

for (let i = 0; i <= 1000000; i++) {

arr.push(10);

}

await new Promise((resolve) => {

setTimeout(resolve, 50);

});

await new Promise((resolve) => {

setTimeout(resolve, 50);

});

res.json({ success: true });

});

app.listen(3000);

Benchmark result:

Requests per second: 85.87 [#/sec] (mean)

Time per request: 1164.554 [ms] (mean)

This caused the biggest hit on throughput. Every request allocated an array of one million elements, so the new-space gets full all the time, so the garbage collector will run the minor GC a lot, and when the garbage collector runs our code does not.

One key note from this examples is to think of cost in a cascading way. Our performance is measured in throughput not in isolated scenarios.

In a way, it’s kinda known that doing O(N^2) operations is not ideal performance-wise, and sequentially doing network requests will increase latency. But, what might fly under the radar is the cost of the garbage collector if we’re not careful of how we allocate memory. Every single memory allocation has some overhead, so we should approach them with care.

Also, that huge initial hit of performance from that O(N) operation is meant to signal the fragility of this event-based system. Its whole throughput depends on us executing callbacks quickly by avoiding intensive CPU operation or expensive synchronous APIs that block the thread.

API and workers

Not every optimization problem can be solved by just optimizing algorithms, network trips or the memory footprint of an endpoint. This is where workers come into play.

Let’s say we have a sign-up endpoint, where we add a user in the database and send a welcome to our app email. In order to send that email we use a third-party API. Some notes:

- The welcome to our app email is not critical to the business logic, whats imperative is the user to be added in the database and to be able to log in

- We have no control over the latency of third-party APIs, we can find ourselves having 100ms+ response times for them without being able to do anything

With these two notes in mind, it kinda comes naturally that if we find ourselves with thousands or tens of thousands of users registering every second, we should outsource that email operation to a worker, thus making a pretty substantial improvement to our sign-up endpoint throughput. Instead of making the call to the third-party API, our endpoint will just publish a message via some broker (e.g. RabbitMQ, Kafka) signifing that user X should get an email, and the worker will just listen to messages and attempting to send the emails.

Situations to consider offloading operations to workers:

- Non-critical operations with variable latencies

- CPU intensive operations when using event-based servers

Caching

As a generally rule of thumb requests should get to certain machines or operations only if it’s necessary. Meaning:

- If the client (web/mobile app) needs a new API response only every 10 minutes, it should cache the response and call the API only when it’s necessary

- If a database query rarely changes it’s response, we should cache the response in memory (e.g. via Redis), and serve the data from there

- If we query by a certain field, that query should be indexed (saved in memory and point to the record on disk)

The best optimization we can do to our API is not call it, same for the database or any other machine that spends resources to serve us something.

Conclusion

Because of the event-based approach, Node is similar with NoSQL databases, in the sense that, in certain use cases it will outperform the classic RDBMS (in our case thread-based servers), but the cost of that performance improvement is we’re limited in what operations we can freely do.

This makes it extra important to understand how Node works from a concurrency and memory point of view, because one mistake can absolutely wreck our throughput.

References:

https://nodejs.org/en/docs/guides/blocking-vs-non-blocking

https://nodejs.org/en/docs/guides/event-loop-timers-and-nexttick

https://nodejs.org/en/docs/guides/dont-block-the-event-loop

https://docs.libuv.org/en/v1.x/design.html

https://docs.libuv.org/en/v1.x/threadpool.html#threadpool

https://berb.github.io/diploma-thesis/original/043_threadsevents.html

A Deep Dive Into the Node js Event Loop - Tyler Hawkins

https://stackoverflow.com/questions/61550822/why-node-js-spins-7-threads-per-process

https://v8.dev/blog/trash-talk

https://jayconrod.com/posts/55/a-tour-of-v8-garbage-collection

https://v8.dev/blog/free-garbage-collection

https://deepu.tech/memory-management-in-v8/